Our response to recent study on probiotics

Last week a study was released in the press, including in the Daily Mail, Telegraph and Times, claiming that probiotic drinks and supplements are 'unlikely to have any health benefits'. The study involved scientists from University College London (UCL) who put eight probiotic products, Align, Bio Balance, Bio-Kult and Probio7, Yakult, Actimel, VSL#3, Symprove through three different tests. The tests investigated whether products contained as many live bacteria as claimed on their labels, whether they survived stomach acidity and if they then flourished in the gut. Only one product apparently passed all of the tests.

What we say

Whilst we can’t actually see the full study, we think it's important to put it into context and look at the overall picture. This UCL study appears to have used in-vitro data only, whereas when considering research, it’s clinical trials that are considered key.

Below are the key areas of the study:

Shelf Stability

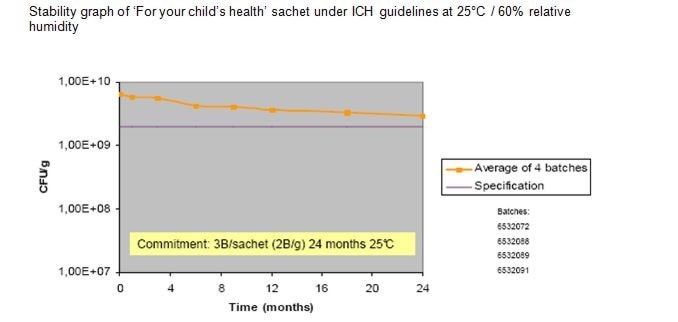

As mentioned, this study looked at three different points. The first tested whether the product contained as many bacteria by the end of its shelf life as it claims. When it comes to testing viability of a probiotic, of course we cannot speak for other companies, but presumably some probiotic products are not tested at all to contain the amount of microorganisms stated on the pack. The next step up would be an accelerated experiment, taking 6 months or so, and subjecting the probiotics to higher temperatures than those expected of the product in reality. From what we are able to glean, a number of probiotics are tested this way. However, you can go yet a step further and test the products using the laborious process of literally leaving the product in carefully controlled conditions for two years and testing at regular intervals by taking a capsule and counting the bacteria present under a microscope! This way you know with confidence that the products have at least, if not more, microorganisms as the amount stated on the packaging by the end of its given shelf life.

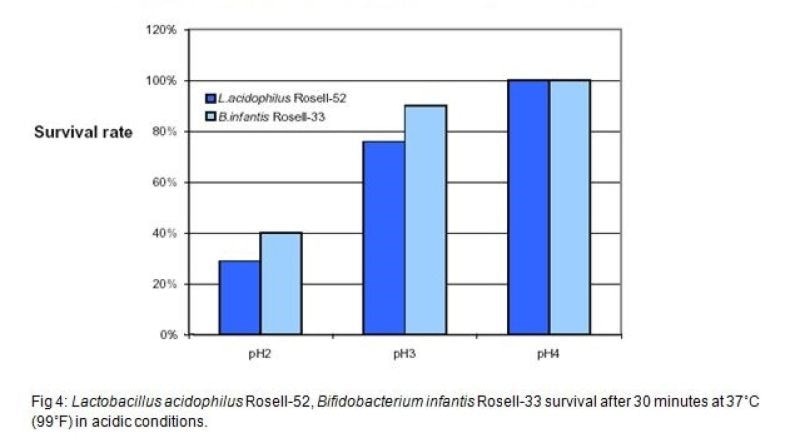

pH survival

Survival is an important factor when selecting a high quality probiotic. Indeed there would be no point in taking a probiotic if the microorganisms were killed off in the stomach acidity, and didn't reach the intended destination (usually the gut)! Hence the second test in this UCL study, looked at whether the bacteria survive the acidic conditions of the stomach. Your stomach pH actually varies over the day, but is of course more acidic rather than neutral or alkaline (so that we can digest food properly, and defend against pathogens entering the system). It is also actually recommended that live cultures be taken at breakfast time when the stomach is less acidic. Some strains, for example Lactobacillus rhamnosus Rosell-11, also have been clinically trialled to show that the bacteria can still be found in stool samples, showing clearly that they have survived the acidic environment of the stomach. Similarly, the strains Lactobacillus rhamnosus GR-1® and Lactobacillus reuteri RC-14® have been extensively researched, and have been tested and found in vaginal swabs - this again demonstrates that the strains survived the stomach acidity, as they reached their intended destination!

Adherence

The final point the study made was that the bacteria, in all but one product, failed to ‘flourish’ and thrive in the gut. In order to flourish we know that generally, the first criteria is to adhere to the gut wall - a factor necessary for colonisation, so we will here look at our tests on adherence. We have plenty of research to show that the strains in our range do in fact adhere to the epithelial cells in the intestine. It is clearly very difficult to measure this adherence without doing intestinal tissue biopsies. Therefore, scientists have developed in-vitro adherence tests with human cells grown in tissue cultures. L. acidophilus NCFM® is particularly well known for its ability to adhere to human epithelial cell lines.

It is worth noting that not all strains work by adherence. S. boulardii for example is not meant to adhere to the gut wall but rather works in a transient manner. Furthermore, adherence can be an interesting testing point in that bacteria can also work by inhibiting pathogens from adhering to cell walls. In-vitro studies show that L. acidophilus Rosell-52 and L. rhamnosus Rosell-11 for example, are both capable of inhibiting the adhesion to intestinal epithelial cells of enteropathogenic E. coli O127:H6 and enterohemorrhagic E. coli O157:H7, which are respectively responsible for prolonged diarrhoea in children and hemorrhagic colitis.

Clinical trials

As mentioned, this study is based on in-vitro tests only. We know that clinical trials are in general given more importance than in-vitro, as at the end of the day, you can do plenty of tests in a test tube, but it is very difficult to replicate the effect of a supplement or medicine once in the human body. This is what clinical trials are for. There is growing evidence in the form of clinical trials to suggest that various probiotic strains do have health benefits. It would then be logical to point out that for clinical trials to show that the strains have health benefits they would have had to colonise the gut.

And then there is the lesser known fact about strain specificity. The study did not go into the difference between strains of live bacteria and that in fact they all have different roles to play. This is key, as one strain which works in one area, may have no effect on another. For example, Lactobacillus rhamnosus GR-1® has been proven to colonise the vaginal tract and be effective in helping to alleviate cystitis, but this particular strain is not proven to colonise the gut and is thought to play little role there.

Are probiotic drinks better than supplements?

One of the apparent conclusions of this study is that drinks are better than supplements. We find this a little subjective for two reasons. Firstly, two out of three of the probiotic drink products supposedly failed the tests so it seems a confusing that they should be considered better. And secondly, very simply put, if you want a probiotic to work, you need to find the specific strain for the function you want to achieve.

Surely the proof is in the pudding? The probiotic industry is not growing purely because of marketing, but rather because the research covering the enormous impact of our microflora is growing at a fast pace, and as importantly because consumers actually find they work. It’s not all doom and gloom. We are pleased to see an article published in the Daily Mail today recognising the value of probiotics for a variety of health issues as long as from a reputable source.

References

- http://www.dailymail.co.uk/health/article-2752798/The-probiotic-drinks-don-t-bring-benefits-Study-finds-good-bacteria-products-does-not-reach-small-intestine.html

- http://www.telegraph.co.uk/health/healthnews/11091887/Probiotics-how-each-fared-and-what-they-contain.html

- http://www.thetimes.co.uk/tto/science/article4204202.ece

- First image: www.after10thwhat.com