Taking Probiotics During Pregnancy

Alongside eating a healthy diet, many pregnant women look for other ways to support their own health and the health of their unborn child during pregnancy. Supplementing with folic acid and vitamin D is recommended, but to further enhance wellbeing, many expectant mothers choose to take a supplement containing probiotics. Specific, well-researched strains of beneficial bacteria can positively influence different areas of health at this very special time.

Read on to find out everything you need to know about taking probiotics during pregnancy:

- Benefits of taking probiotics in pregnancy

- Are probiotics safe to take in pregnancy?

- How do probiotics work during pregnancy?

- When should I start taking probiotics in pregnancy?

- Summary of probiotics during pregnancy

Benefits of probiotics during pregnancy

Expectant mothers can support many aspects of their health naturally by taking probiotics during pregnancy. They may find their digestion is just not the same, or they may want to boost their immune system or avoid developing health conditions they had suffered in a previous pregnancy. To read more about how probiotics can support in many ways, including for vaginal and digestive health, take a look at our article: Benefits of probiotics.

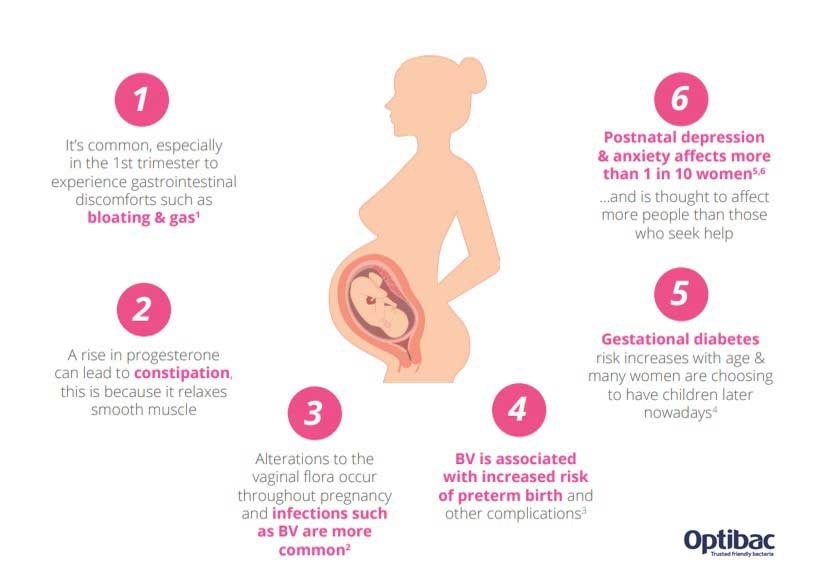

The benefits of probiotics during pregnancy are far-reaching, influencing the following areas:

- Vaginal health

- Mental wellbeing

- General immunity

- Gestational diabetes

- IBS and bloating

- Occasional constipation

- Morning sickness

Let’s take a look at some of these common pregnancy worries and what may help.

Intimate health in pregnancy

Why is this important? Vaginal infections can result in unwanted pregnancy complications. Therefore, pregnant women need to take care of their vaginal health, even before conception. Common over-the-counter medications can be useful to gain relief from an infection. However, they often only treat the symptoms rather than the root cause. Probiotics that are known to reach the vaginal tract can promote a healthy vaginal microbiome, which in turn may lower the risk of vaginal infections.

Strain focus:

Combination of Lactobacillus rhamnosus GR-1® and Lactobacillus reuteri RC-14®: These two strains are the most researched strains for vaginal health. They’ve been researched in pregnant women and shown to reach the vaginal tract, even when taken orally. They have been shown to reduce the number of urinary tract infections and improve symptoms associated with bacterial vaginosis and thrush14,15,16.

Combination of Lactobacillus rhamnosus HN001 and Lactobacillus acidophilus La-14®: These two strains have been researched in women with bacterial vaginosis and thrush. Together, they have improved symptoms and reduced the risk of recurrent infections17,18,19.

Healthcare practitioners can find out more about these strains on the Probiotics Database: Lactobacillus rhamnosus GR-1®, Lactobacillus reuteri RC-14® & Lactobacillus rhamnosus HN001.

Postnatal depression and mood

Why is this important? According to the NHS, it is thought that at least 1 in 10 women suffers from postnatal depression20. The exact cause is unknown and is likely due to many different reasons, one of which could be the changes we see in the gut microbiome and consequent inflammation. There is a strong connection between the gut and brain (known as the gut-brain axis), so any changes to the gut environment can in turn affect our mood. The gut is also responsible for making many necessary chemicals, including serotonin (often referred to as the 'happy hormone', though in actual fact it is a neurotransmitter).

Strain focus:

Lactobacillus rhamnosus HN001: This is one of the very few probiotic strains to be trialled specifically for postnatal depression. A gold standard trial including 380 pregnant women found L. rhamnosus HN001 was able to significantly lower depression and anxiety scores. The probiotic was taken during pregnancy and for six months post-birth21.

Additionally, this strain was shown to improve mental health scores and ‘social functioning’ in pre-diabetic patients. During this double-blinded, randomised 12 weeks study22 participants were either given Lactobacillus rhamnosus HN001 or placebo at the same time as following an intermittent fasting regime. The probiotic group saw statistically significant improvements to their mood and mental health scores.

Healthcare professionals can read more about Pregnancy and Mental Health here.

General immunity in pregnancy

Why is this important? Pregnant women are more susceptible to coughs and colds, and this can be even more of a worry in the first trimester. However, there are actually not many choices available to pregnant women to boost their immune health. As 70% of the immune system lies in the gut, maintaining good gut health is vital. Some probiotic strains have been shown to reduce the risk of infections, boost immune cells, and reduce severity of, or recovery time from, an infection.

Strain focus:

Lactobacillus paracasei CASEI 431®: This strain has been trialled in thousands of individuals and has been shown to improve the immune system and reduce recovery time by an average of three days23.

Healthcare practitioners can find out more about this strain on the Probiotics Database: Lactobacillus paracasei CASEI 431®.

Gestational diabetes (GD)

Why is this important? By the third trimester, the microbiome may resemble someone with diabetes or metabolic syndrome. These changes are considered natural and part of pregnancy. Problems may arise, however, if a woman has existing problems with insulin management, as this can increase her risk of GD. For example, women over the age of 35, women with a high BMI, and women who had GD in previous pregnancies may all be at higher risk. GD can be tricky to manage and can cause further health implications for both mum and baby. Health professionals can find out more on the Probiotic Professionals site: Can 'Synbiotics' improve symtoms of gestational diabetes?

Strain focus:

Lactobacillus rhamnosus HN001: This is one of only a few strains of probiotics to have research on GD. Pregnant women who took this probiotic during pregnancy had a generally reduced risk of GD. The findings were significant for women at higher risks, e.g. those over 35 and women who developed GD in previous pregnancies. In fact, no women in the study developed GD even if they had had it previously24.

IBS & bloating in pregnancy

Why is this important? One uncomfortable side effect of the increase in progesterone during pregnancy is that it can cause excessive bloating. Progesterone causes the smooth muscles of the intestinal wall to relax, meaning that food does not pass through as quickly. Slower digestive transit time allows for greater fermentation in the gut, which increases gas production and thus bloating. Many pregnant women also find their IBS is exacerbated during pregnancy; this is likely due to the hormonal and microbial changes at play. As they are supporting another life, it’s really important that pregnant women look after their gut health to ensure they are digesting and absorbing their nutrients well. Probiotics can increase the production of digestive enzymes, to help break down foods and protect our gut cells to support good absorption rates. Poor gut health can result in poorly digested food and might mean that additional pregnancy supplements are not efficiently absorbed. If you would like to read about probiotics and IBS in more detail, read our article Which Probiotics are for IBS?

Strain focus:

Lactobacillus acidophilus NCFM®: This is one of the most researched probiotic strains for digestive health. It’s been shown to bind to gut cells, support a healthy gut environment and significantly improve abdominal pain and bloating25.

Lactobacillus casei Shirota®: A well-researched strain supporting gut function. The strain has been shown to improve IBS symptoms and increase the numbers of friendly bacteria in the gut26.

Bifidobacterium infantis 35624: This strain has shown good results for IBS. In a gold standard trial, it was shown to improve overall IBS symptoms, particularly abdominal pain and bloating27.

Healthcare practitioners can find out more about these strains on the Probiotics Database: Lactobacillus acidophilus NCFM®, Lactobacillus casei Shirota® & Bifidobacterium infantis 35624.

Constipation in pregnancy

Why is this important? High levels of pregnancy hormones such as progesterone can cause constipation. In addition, reduced levels of friendly bacteria can affect the overall gut environment, which can slow down gut movements. Often pregnant women do not want to take pharmaceutical laxatives, as their long-term use can lead to a lazy gut. However, probiotics are gentle and non-habit forming, so offer a natural option.

Strain focus:

Bifidobacterium lactis HN019: This strain has been highly researched to improve constipation & gut transit times, and to promote healthy gut function12. It has been trialled in hundreds of pregnant women and also supports a range of other GI issues, including flatulence and abdominal pain.

Bifidobacterium lactis BB-12®: This strain has been researched in thousands of individuals, and has been shown to ease constipation and increase the number of bowel movements each week13.

Healthcare practitioners can find out more about Bifidobacterium lactis BB-12® on the Probiotics Database.

Prebiotics can also ease constipation. When prebiotics are used in the gut by friendly bacteria, the bacteria produce short-chain fatty acids which can stimulate natural bowel movements and promote a healthy gut environment.

Morning sickness in pregnancy

Why is this important? The increase in pregnancy hormones can cause nausea and sickness, particularly during the first trimester. There is no research specifically looking into probiotics and morning sickness. B. lactis HN019 has been shown to reduce nausea in non-pregnant women, so this may be of benefit12. Often pregnant women with nausea or sickness tend to have low energy levels and the sickness may impact their gut microbiome. Taking a probiotic helps to top up the levels of friendly bacteria and boost energy levels.

Are probiotics safe in pregnancy?

This is the question that is first in the minds of all newly expectant mums looking to add probiotics to their health regime: are probiotics safe to take when pregnant or breastfeeding?

Generally, probiotics and prebiotics are considered safe during pregnancy, as confirmed by the results of large scientific studies1,2. A number of organisations including Babycentre UK29 and the American Pregnancy Association30 have also suggested probiotic supplementation during pregnancy to be safe and beneficial.

However, there is still one probiotic in particular, Saccharomyces boulardii, that is lacking in clinical research in pregnant women. This unique probiotic strain has shown many positive health benefits, including reducing diarrhoea, exerting anti-inflammatory effects and inhibiting the growth of harmful bugs; but due to a lack of testing in this one vulnerable subset of the population, pregnant women should exercise caution when considering this probiotic. Some researchers have therefore suggested not to use it at all, or to check with a doctor before using it.

Healthcare practitioners can find out more about Saccharomyces boulardii on the Probiotics Database.

With the exception of Saccharomyces boulardii, probiotics are confirmed to be safe for use during pregnancy; however, expectant mums who are considered more 'at risk’, or those with a health condition (especially one related to the immune system) should always check with their GP before taking any supplement, including probiotics.

If you are generally well and healthy and would like to take a probiotic, always check with the manufacturer’s guidelines, especially if it is not a probiotic designed for use during pregnancy, and ensure the probiotic strains are suitable. If in doubt, give the brand a call.

How do probiotics work during pregnancy?

In general, probiotics help to rebalance the microbiome by topping up with levels of friendly bacteria. Once in the gut, they can do many different jobs and support many aspects of health. Probiotics can be used by most people of all age groups.

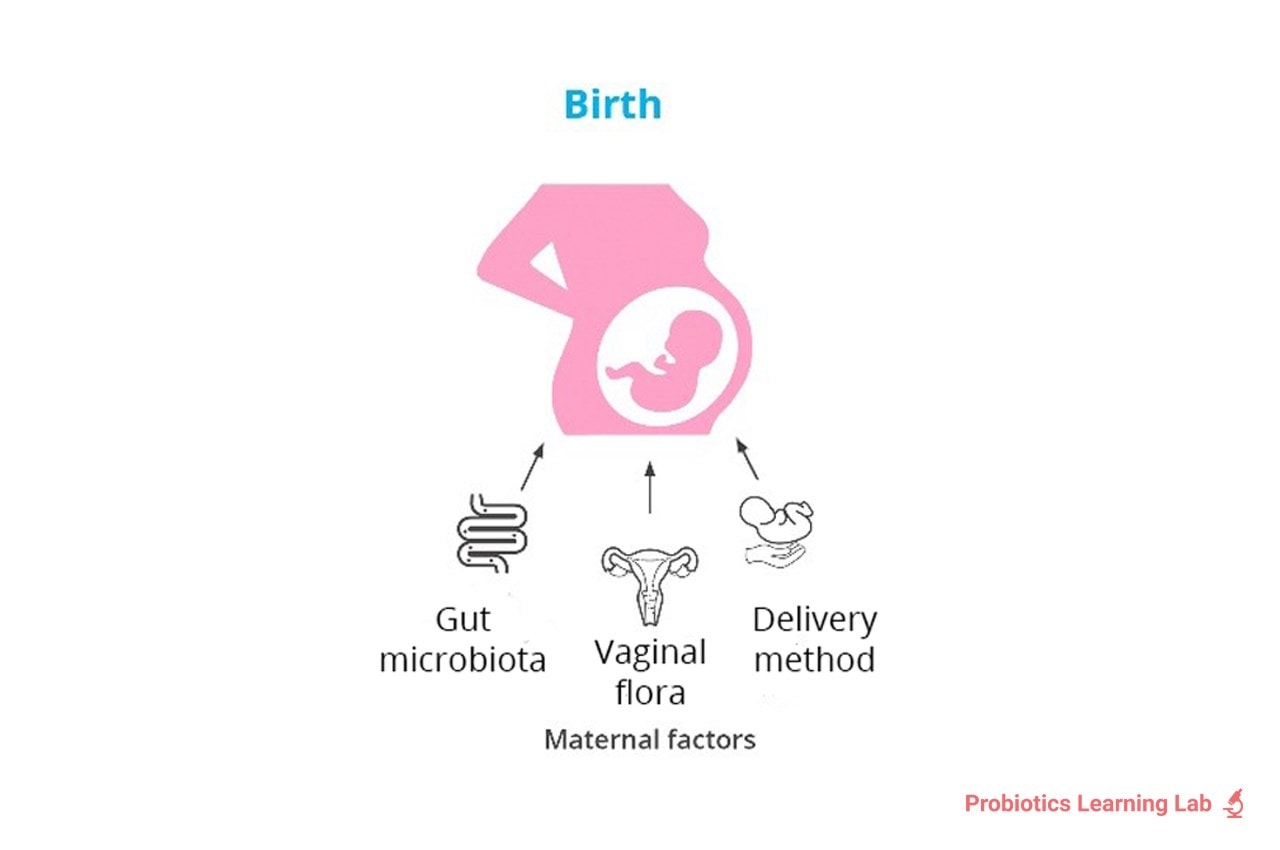

Pregnancy forms part of the first 1000 days of life - more detail on this can be found in our article Baby Probiotics. A mother’s microbiome is believed to play an important role in both hers and her baby’s health. When a baby passes through the birthing canal, they are exposed to thousands of microbes. It’s therefore important for mum to have lots of good bacteria to transfer to the newborn. Even breast milk contains friendly microbes that can seed an infant’s gut.

So, to understand how probiotics may be beneficial during pregnancy, we need to understand what happens to the microbiome throughout the trimesters.

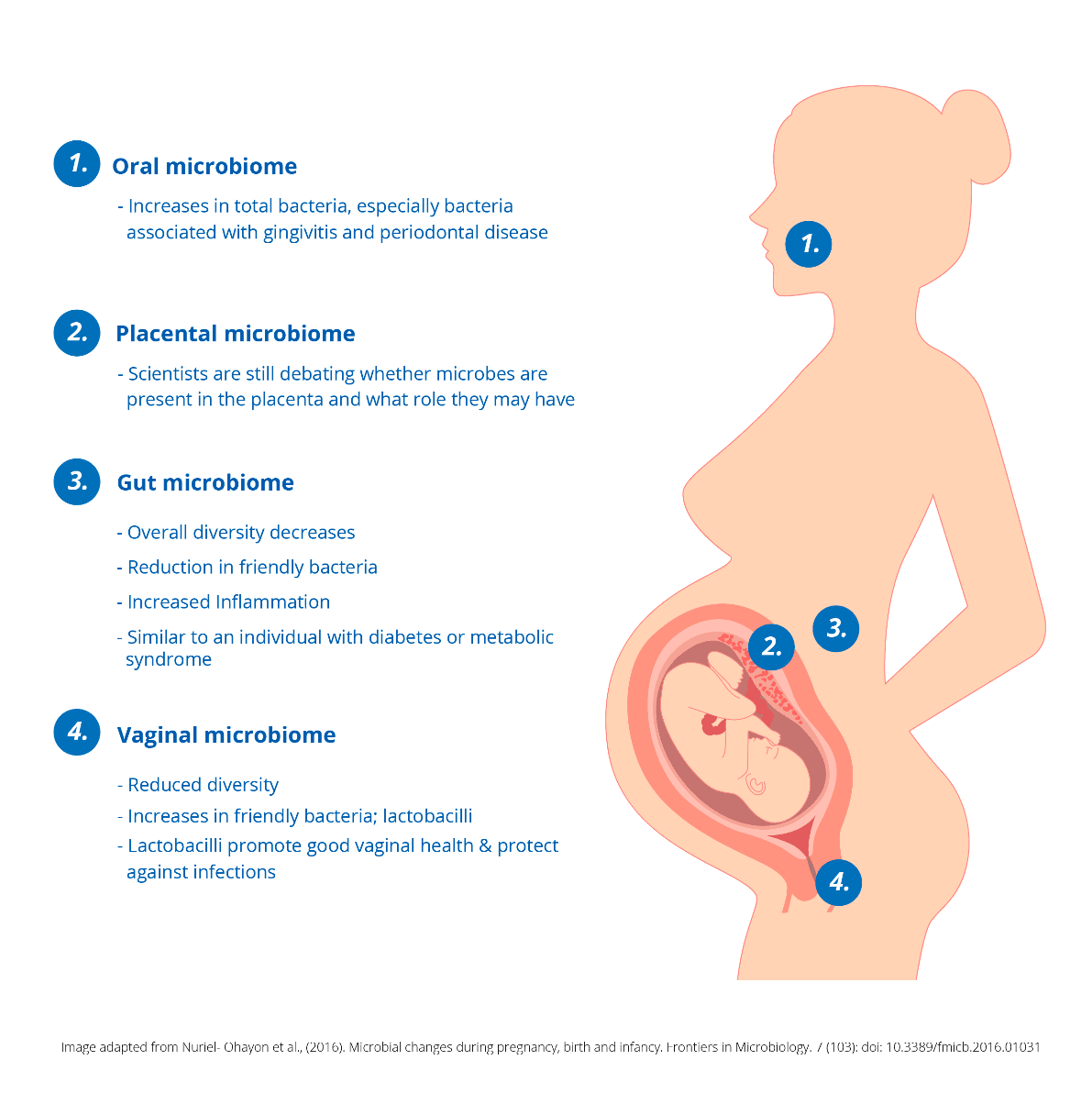

During pregnancy, there are many microbial, immunological, hormonal and metabolic changes, which all influence one another. We actually see some big changes to the microbiome, too. There are still some mixed reports regarding how the gut microbiome composition changes, but the following is generally accepted amongst scientists:

1. Oral microbiome: An upcoming area of research is the changes to the oral microbiome. Pregnant women are at higher risks of oral health issues. This could be because the number of bacteria in the oral cavity increase, including bacteria associated with gingivitis and periodontal disease8.

2. Placental microbiome: There is some promising evidence to suggest that placental microbes are present, though this is disputed within the scientific community. In some cases, parts of microbes or DNA fragments have been found, leading scientists to ask: if microbes are present, what role do they have?

3. Gut microbiome: Overall research suggests that as pregnancy progresses towards the third trimester, we see significant microbial changes. In fact, one study showed when a poo sample from a pregnant woman in her third trimester was given to a sterile (germ-free) mouse, the mouse gained weight and the microbiome looked like that of an individual with metabolic syndrome or diabetes3. These changes are regarded as a normal part of pregnancy; however, in some women, this could explain why gestational diabetes occurs. The same study also found a reduction in diversity and friendly bacteria, plus higher levels of inflammation. It’s not surprising that these microbial changes, plus hormone increases, cause a lot of GI upset in pregnant women!

4. Vaginal microbiome: As pregnancy progresses, the vaginal microbiome becomes less diverse and more dominant in friendly bacteria known as lactobacilli4. Lactobacilli have many protective effects; they help to create an environment for friendly microbes to thrive and inhibit the growth of many harmful ones. This is particularly important as vaginal infections, such as bacterial vaginosis (BV) or thrush, may increase the risk of recurrent miscarriages and pre-term births5,6,7. You can read more about vaginal health in: All About Your Vaginal Flora.

On top of all these natural changes, the microbiome can also be further affected by stress levels, diet and antibiotic use. These may impact mum and baby’s health during gestation and post-birth. For example, antibiotic use during pregnancy has been associated with higher numbers of harmful bugs (such as Escherichia coli and Staphylococcus spp.) in the vaginal tract9. High levels of these bugs in new-borns have been associated with colic, eczema and allergies10,11. To learn more, health professionals can read this article on our sister site, Probiotic Professionals: Antibiotics during pregnancy may impair baby's immunity.

Ultimately, stress, diet and antibiotic use, amongst other factors, can reduce the level of friendly bacteria, causing microbial imbalances (dysbiosis). So, probiotics have a lot of potential to balance the microbiome and support overall health.

The role of probiotics during pregnancy

Placental microbiome and preterm births

Research has shown that the microbial composition of the placenta differs between preterm (before 37 weeks) and full-term (40 weeks) births32. This difference may explain why preterm babies face a higher risk of neurological and respiratory complications, as it is hypothesised that microbes from the placenta contribute to critical brain and lung development in the final weeks of pregnancy. The potential role of probiotics in supporting a healthy placental microbiome remains an area of active investigation.

Maternal microbiome and immune function

The maternal microbiome is closely linked to immune function, metabolism, and overall well-being. Certain probiotic strains have been studied for their potential to enhance maternal health and influence the baby’s microbiome even before birth. A human clinical trial found that supplementation with Lactobacillus rhamnosus HN001 during pregnancy increased immune markers in placental cord blood and breast milk33. This suggests a potential role in supporting maternal immune function while also influencing early immune development in the baby.

Additionally, an in vitro study demonstrated that Lactobacillus acidophilus Rosell-52 can adhere to the cervical lining, suggesting a role in priming the mother’s microbiome before birth34. This may contribute to the natural transfer of beneficial bacteria from mother to baby, particularly during vaginal delivery.

Probiotics and C-section births

Studies indicate that babies born via C-section may have different microbiome development compared to those delivered vaginally, as they miss the initial exposure to maternal vaginal and gut bacteria. Some research suggests that probiotic supplementation during pregnancy could help support microbial transfer, even in cases where a natural birth is not possible.

When should I start taking probiotics in pregnancy?

Probiotics may have more benefit the earlier they are taken in pregnancy. The study on gestational diabetes, for example, was given to women at about 14-16 weeks. Studies looking into allergies & eczema in babies & children also found that supplementation in pregnancy from 14 weeks was beneficial. Other research has shown that supplementation in the last month of pregnancy also offered protective effects against eczema & allergies, and supported immune development in the newborn28,29. Probiotics to support vaginal health should also be taken sooner rather than later, but really it is never too late, or too early!

Hopefully, all this information has highlighted how probiotics and pregnancy can go hand in hand for a natural and effective choice to support a pregnant woman’s health. Pregnancy forms part of the first 1000 days of life so can have a huge effect on baby’s health, both in the womb and after birth. A happy and healthy mum increases the chance of a happy and healthy baby!

Remember: if in doubt about the research, safety or when to start, always contact the probiotic brand to discuss options to best suit your needs in terms of pregnancy and probiotics. Side effects of probiotics for women are rare, making these supplements an attractive option for supporting health during pregnancy.

Summary of probiotics during pregnancy

- Generally, taking probiotics when pregnant is considered safe, however, one probiotic yeast, Saccharomyces boulardii, is lacking in clinical research in pregnant women.

- During pregnancy, four key areas of the body undergo microbial changes so taking a probiotic in pregnancy may help to bring balance.

- The benefits of taking probiotics in pregnancy are far reaching and can help to support vaginal health, mental wellbeing, general immunity, gestational diabetes, IBS and bloating, occasional constipation and even morning sickness.

- Different strains do different things, so, in terms of the best probiotics for pregnancy it’s a good idea to select a probiotic for pregnant women or one that has been studied for the health concern you are looking to address.

- It’s ideal to start taking a pregnancy probiotic from conception or as early on as possible. You can continue to take certain strains right through till at least 6 months after birth, however, do check that the strains are suitable in pregnancy and breastfeeding.

This article forms part 3 in our educational resource, ‘Early life microbiome series’, where we take you on a journey through the development and support of the microbiome from conception through to young adulthood. The other articles in this series are:

- All About The Microbiome

- Child Microbiome: Dr Kate's Guide - this explores the factors affecting the microbiomeside in childhood

- Probiotics for Pregnancy

- Baby Probiotics

- Probiotics for Kids

- Probiotics for Teenagers

If you enjoyed this article, you might also be interested in:

Pregnancy & the Vaginal Microflora

Getting Pregnant: Could Probiotics Help?

Maternal Gut Bacteria For Baby

References

- Elias J et al., "Are probiotics safe for use during pregnancy and lactation?," Can Fam Physician, pp. 57 (3): 299-301, 2011.

- Dugoua J et al., "Probiotic safety in pregnancy: a systematic review and meta analysis of randomised controlled trials of Lactobacillus, Bifidobacterium and Saccharomyces spp.," J Obstet Gynaecol Can, pp. 31 (6): 542-552, 2009.

- Koren O et al., "Host remodeling of the gut microbiome and metabolic changes during pregnancy," Cell, pp. 150 (3): 470-480, 2012.

- Aagaard K et al., "). A metagenomic approach to characterization of the vaginal microbiome signature in pregnancy," PLoS ONE, p. 7:e36466, 2012.

- DiGuilio DB et al., "Prevalence and diversity of microbes in the amniotic fluid, the fetal inflammatory response, and pregnancy outcome in women with preterm pre-labor rupture of membranes," Am J Reprod Immunol, pp. 64: 38-57, 2010.

- Farr A et al., "Effect of asymptomatic vaginal colonization with Candida albicans on pregnancy outcome," Acta Obstet Gynecol Scand, p. 94:989–996., 2015.

- Zhang et al., "Alteration of vaginal microbiota in patients with unexplained recurrent miscarriage," Exp Ther Med. , p. 17(5): 3307–3316, 2019.

- Fujiwara N et al., "Significant increase of oral bacteria in the early pregnancy period in Japanese women.," J. Investig. Clin. Dent, p. doi: 10.1111/jicd.12189, 2015.

- Stokholm et al., "Antibiotic use during pregnancy alters the commensal vaginal microbiota," Clinical Microbiology and Infection, pp. 20 (7): 629-635, 2014.

- Dubois N et al., "Characterising the intestinal microbiome in infantile colic: findings based on an integrative review of the literature," Biological Research for Nursing , p. 18 (3): doi:10.1177/1099800415620840, 2016.

- Wong B et al., "Exploring the Science behind Bifidobacterium breve M-16V in infant health.," Nutrients, p. 11 (8); 1724 doi: 10.3390/nu11081724, 2019.

- Waller P et al., "Dose-response effect of Bifidobacterium lactis HN019 on whole gut," Scandinavian Journal of Gastroenterology,, p. 46: 1057–1064, 2011.

- Eskesen D et al., "Effect of the probiotic strain Bifidobacterium animalis subsp. lactis, BB-12®, on defecation frequency in healthy subjects with low defecation frequency and abdominal discomfort: a randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled, parallel-group trial," British Journal of Nutrition , p. doi:10.1017/S0007114515003347, 2015 .

- Beerepoot M et al., "Lactobacilli vs antibiotics to prevent urinary tract infections: a randomized, double-blind, noninferiority trial in postmenopausal women," Arch Intern Med, vol. 172, no. 9, pp. 704-712, 2012.

- Martinez M et al., "Improved treatment of vulvovaginal candidiasis with f********** plus probiotic Lactobacillus rhamnosus GR-1® and Lactobacillus reuteri RC-14®," Lett Appl Microbiol., vol. 48, no. 3, pp. 269-74., 2009.

- Anukam K et al., "Augmentation of antimicrobioal m************ therapy of bacterial vaginosis with oral probiotic Lactobacillus rhamnosus GR-1® and Lactobacilus reuteri RC-14®: randomized,," Microbes Infect., vol. 8, no. 6, pp. 1450-4., 2006.

- Russo R et al., "Study on the effects of an oral lactobacilli and lactoferrin complex in women with intermediate vaginal microbiota," Archives of Gynacology and Obstetrics, pp. doi: 10.1007/s00404-0.18-4771-z, 2018.

- Russo R et al., "Randomised clinical trial in women with recurrent vulvovaginal candidiasis: efficacy of probiotics and lactoferrin as maintenance treatment," Mycoses, p. DOI: 10.1111/myc.12883, 2019a.

- Russo R et al., "Evidence based mixture containing Lactobacillus strains and lactoferrin to prevent recurrent bacterial vaginosis: a double blind, placebo controlled, randomised clinical trial," Beneficial Microbes, pp. 10 (1): 19-26, 2019b.

- NHS, "Overview: Postnatal Depression," 12 December 2018. . Available: https://www.nhs.uk/conditions/post-natal-depression/.

- Slykerman R et al., "Effect of Lactobacillus rhamnosus HN001 in pregnancy on postpartum symptoms of depression and anxiety: a randomised double blind placebo controlled trial," EBioMedicine, pp. 24, 159-165, 2017.

- Murphy, R. et al. (2020) 'A Randomized Trial Assessing the Effects of Intermittent Fasting and Lacticaseibacillus rhamnosus Probiotic among People with Prediabetes'. Nutrients. 12(11), 3530; https://doi.org/10.3390/nu12113530

- Jesperson et al., "Effect of Lactobacillus paracasei subsp. paracasei, L. casei 431 on immune response to influenza vaccination and upper respiratory tract infections in healthy adult volunteers: a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled, parallel-group study," AJCN, vol. 101, no. 6, pp. 1188- 1196, 2015 .

- Wickens K et al., "Early pregnancy probiotic supplementation with Lactobacillus rhamnosus HN001 may reduce the prevalence of gestational diabetes mellitus: a randomised controlled trial," British Journal of Nutrition, pp. 117, 804-813, 2017.

- Lyra et al., "Irritable bowel syndrome symptom severity improves equally with probiotic and placebo," World Journal of Gastroenterology, vol. 22, no. 48, pp. 10631-10642, 2016.

- Thijssen AY et al., "A randomized, placebo-controlled double blind study to assess the efficacy of a probiotic dairy product containing Lactobacillus casei Shirota on symptoms of irritable bowel syndrome," Gastroenterology,, vol. 140, p. S609, 2011.

- Whorwell P et al., "Efficacy of an encapsulated probiotic Bifidobacterium infantis 35624 in women with irritable bowel syndrome," American Journal of Gastroenterology, vol. 101, pp. 1581-1590, 2006.

- Wickens K et al., "A differential effect of 2 probiotics in the prevention of eczema and atopy: a double blind, randomised, placebo controlled trial," Atopic dermatitis and skin disease, pp. 122 (4): 788-794, 2008.

- Prescott SL et al., "Supplementation with Lactobacillus rhamnosus or Bifidobacterium lactis probiotics in pregnancy increases cord blood IFNy and breast milk transforming growth factor B and immunoglobin A detection," Clinical and experimental Allergy , pp. 38 (10): 1606- 1614, 2008.

- BabyCentre Medical Advisory Board, "Probiotics and prebiotics in pregnancy," 2020. https://www.babycentre.co.uk/a1025252/probiotics-and-prebiotics-in-pregnancy

- American Pregnancy Association, "Probiotics During Pregnancy," 2020. https://americanpregnancy.org/pregnancy-health/probiotics-during-pregnancy/

- Aagaard K, et al (2014) The Placenta Harbors a Unique Microbiome . J Sci Transl Med. 21;6(237).

- Prescott SL et al. (2008). Supplementation with Lactobacillus rhamnosus or Bifidobacterium lactis probiotics in pregnancy increases cord blood IFNy and breast milk transforming growth factor B and immunoglobin A detection. Clinical and experimental Allergy , 38 (10): 1606- 1614.

- Atassi F. et al. (2006). In vitro antibacterial activity of Lactobacillus helveticus strain against diarrhoeagenic, uropathogenic and vaginosis-associated bacteria. Journal of Applied Microbiology. 101 647–654

Popular Articles

View all Women's Health articles-

Children's Health16 Nov 2023

-

Women's Health18 Apr 2024