What are Human Strains?

When discussing probiotics, the term “human strains” is a rather vague one. It typically refers to a probiotic strain that is originally derived from the human body.

- Are human strains superior?

- Probiotic Myths: BUSTED

- The origin of a probiotic strain: does it matter?

- Dairy intolerance or allergy

Are human strains superior?

The scientific definition of a probiotic ("A live microorganism which when administered in adequate amounts confers a health benefit on the host" ) does not stipulate that the microbe must have a human origin, or be a “human strain”. Probiotics must be able to exert their benefits on the host through growth and/or activity in the human body (Collins et al., 1998; Morelli, 2000).

It is therefore the action, and not the source of the probiotic microorganism that is a key factor in choosing a probiotic. The ability of a probiotic strain to remain viable at the target site and to be effective in the human gut should always be verified and tested.

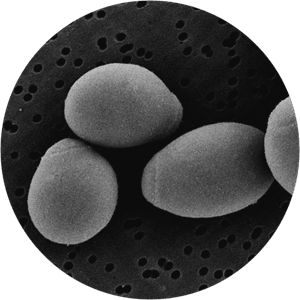

There are in fact many examples of effective probiotic strains which are not recognised as normal residents of the human gastrointestinal tract. For example, Saccharomyces boulardii - was originally extracted from fruit and therefore not a “human strain”

This probiotic yeast has been shown in numerous clinical trials1 to benefit human consumers. In fact it is one of the best established probiotics on the market today, with reams of clinical research behind it - especially demonstrating its ability to support health in those with conditions such as inflammation or diarrhoea.

When deciding the superiority of a probiotic, the most logical area to focus on is the research behind it.

- Has this specific strain been tested and shown to survive through stomach acidity?

- Has it been tested and shown to have an ability to bind to the cells of the gut wall?

- Has the specific strain been tested in a clinical setting - ie. consumed by humans, preferably in a placebo-controlled, randomised and gold standard clinical trial - and shown to have a health benefit? (Read more about probiotic research here).

There is no existing scientific evidence to show that human strains are more capable of binding to the gut wall lining, or colonising the gut, or exerting a health benefit - than 'non human' strains. As mentioned above, some of the best researched probiotic strains, such as S. boulardii, do not have a human origin.

Probiotic Myths: BUSTED

As probiotics are still a relatively novel area of human health, many misconceptions (such as the idea that human strains are better than non human strains) exist regarding what determines a high quality probiotic. If you are finding this an interesting read, you may enjoy browsing our Probiotic Myths: BUSTED pages which dispel some of the most common misconceptions, using evidence and clinical research to do so.

The origin of a probiotic strain: does it matter?

Still unsure? As touched on above, the 'origin' of a probiotic strain refers to the place it was originally isolated (eg. human gut, fruit, dairy, kefir etc). However this does not necessarily mean the strain in question can only be found in that place, and it certainly does not mean that the bacteria in your supplement was taken directly from that original source.

There are 2 points to bear in mind here:

1. Many of the strains which we use as probiotics today were identified, isolated and 'banked' many years ago, meaning that the bacteria in your supplement are many 'generations' on from the original one isolated some years prior.

- The bacteria in your supplement are not taken from the original source every time they need to be fermented and encapsulated. Swabs are instead taken from the bacteria bank where the strain is registered, and cultured from there.

2. Since then, scientists have discovered that many of these strains are in fact found in other places too, and are not limited to where they were originally found. A microbiologist recently asked the question 'if we eat bacteria in dairy, are those strains now found in humans too?'

- It is important to remember that bacteria are all around us, and that we are continuously influenced by the bacteria in our environment.

Looking as far back as the origin of a strain seems of little significance when seeking a probiotic. Efficacy is the most important thing when it comes to probiotics - and whilst 'origins', or 'human strains' are vague and sometimes unknown, consumers are better off spending time asking other questions, such as: 'What strain of probiotic is this?'; 'Has it been tested and shown to survive stomach acidity?'; 'Has it been clinically trialled for my individual health complaint?', and so on.

Dairy intolerance or allergy

NB. For those with dairy sensitivities or allergies, again the origin of the probiotic strain is not the relevant consideration. Instead you need to be sure of the 'culture' that the probiotic was grown on. Some probiotics use dairy as part of the growing medium, and therefore the end product may contain small traces of dairy and are not recommended for vegans or those who are severely allergic to dairy.

However, the amount of dairy remaining (if any) is usually negligible, and probiotics aid the digestion of lactose, so these would be suitable for people who are simply lactose intolerant.

References

- McFarland, L. V. & Bernasconi, P. (1993) Saccharomyces boulardii: A review of an innovative biotherapeutic agent. Microbial Ecology in Health and Disease; Vol. 6. pp. 157-171.

Popular Articles

View all Probiotics articles-

General Health18 Feb 2025

-

Probiotics11 Oct 2023

-

Prebiotics13 Mar 2024