C. difficile and Probiotics

C. diff infections are unfortunately quite common and can often be serious. Antibiotics are the primary conventional treatment, but there is a growing interest in natural options. Could probiotics help with C. diff? Read on to find out everything you need to know about C. diff and how probiotics might help.

We’ll look at the following areas:

- What is Clostridium difficile?

- Will probiotics help with C. difficile?

- What are the best probiotics for C. diff recovery?

- Can probiotics make C.diff worse?

- Faecal transplants and C.diff?

What is Clostridium difficile?

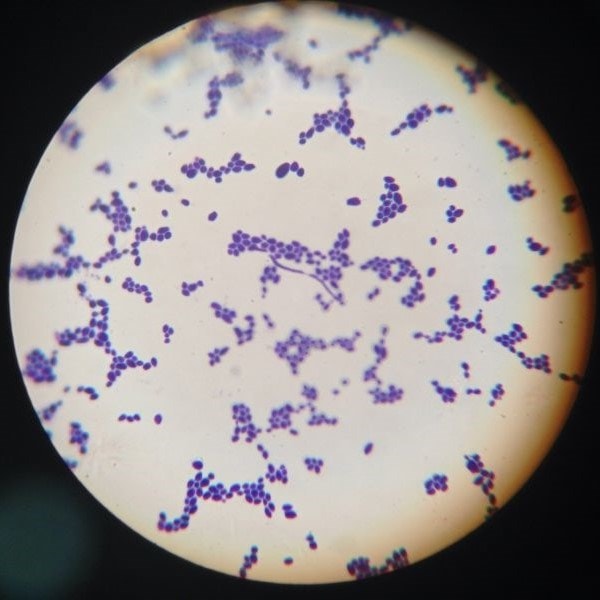

Clostridium difficile (C. difficile or C. diff) is a species of bacteria. Though still often referred to as Clostridium difficile, following its reclassification in 20161, this bacterium is now known as Clostridioides difficile. As it is most commonly abbreviated to C. diff, this reclassification is unknown to some people, but it is important to use the correct term if you want to search for the latest news and research.

C. diff is naturally present in the gut of around 60% of children under the age of 1 years old and in 3% of adults.2,3 C. difficile does not cause any problems in healthy people with a well-balanced gut microbiota which is able to suppress the Clostridium difficile population and stop it from spreading. Visit the Probiotics Learning Lab to find out more about The Microbiome.

However, the infection is often associated with antibiotic use. Antibiotics that are used to treat other health conditions can cause dysbiosis, a condition where the normal gut microbiota is disrupted; compromising a vital part of our immune system and allowing C. difficile to multiply which can result in infections that can in some cases prove fatal. Read this article on the Probiotics Learning Lab to find out more about dysbiosis.

Once it takes hold, a C. diff infection can be very serious. Pathogenic strains of C. difficile produce two large protein exotoxins; known simply as toxin A and toxin B.4 These toxins can induce intestinal inflammation, fluid secretion and mucosal injury.5,6 This can result in conditions such as C. difficile-associated diarrhoea (CDAD) and, in more serious cases, colonic damage and pseudomembranous colitis.7

Clostridium difficile/Clostridioides difficile cases occur most commonly in healthcare environments such as hospitals or care homes where patient populations are at higher risk of infection. This serious and unpleasant illness is more prevalent in the elderly or those with serious health conditions, so its onset is even more serious in these vulnerable patients. In the hospital environment, C. difficile is the biggest known cause of infectious diarrhoea in the developed world.8

Will probiotics help with C. difficile?

A recent review of studies into probiotics for C. diff has shown that they help inhibit the proliferation and virulence of C. diff by ensuring a healthy gut microbiome.20 This is positive news, especially as probiotics tend to be well tolerated by most individuals.

It’s hopeful that you won’t get C. diff if you take probiotics, though there are many factors at work in the development of the infection. However, a well-balanced gut microbiota is able to suppress the C. diff population and stop it from spreading. Taking probiotics to support your microbiome is a way of helping your gut microbiome to be balanced.

But can probiotics alone help C. diff? Should you even take probiotics when you have Clostridioides difficile? Research indicates that it’s fine to take probiotics if you have C. diff, and the best results have been shown when probiotics are used as an adjuvant therapy9 alongside other treatments, in all patients at risk of developing Clostridium difficile/Clostridioides difficile.

What are the best probiotics for C. diff recovery?

One particular combination of probiotics, L. acidophilus Rosell-52 and L. rhamnosus Rosell-11, are extremely well researched in the prevention of antibiotic-associated diarrhoea and C. difficile diarrhoea. Another well noted probiotic strain in this area is Saccharomyces boulardii. Read more about these strains on the Probiotics Database.

There are a number of studies show that Saccharomyces boulardii may protect against infection and gastrointestinal inflammation induced by C. difficile.10,11,12 One randomised, placebo-controlled study revealed that S. boulardii, in combination with a standard oral antibiotic, may be more effective in decreasing the likelihood of C. difficile recurrences than standard therapy alone. The efficacy of S. boulardii was significant with a recurrence rate of just 34.6%, compared with 64.7% on placebo.13 In-depth research has also elucidated the mechanism of action of S. boulardii against C. difficile. Studies have shown that S. boulardii may interfere with the pathogenic process of C. difficile by releasing a 54kDa protease which may inactivate C. difficile toxins A and B and lyse colonic receptors. Furthermore, Saccharomyces boulardii is also known to stimulate the host’s intestinal mucosal immune response, by stimulating an increase in secretory IgA.

In addition to the S. boulardii probiotic yeast, results from other clinical trials suggest that bacterial probiotics could also offer benefits for those suffering with Clostridium difficile infection (CDI).

One such randomised controlled trial monitored 33 patients who were suffering from mild to moderate Clostridium difficile infection. Patients in the intervention group were administered with a combination of four different probiotic strains: Lactobacillus acidophilus NCFM®, Lactobacillus paracasei Lpc-37®, Bifidobacterium lactis Bi-07® and Bifidobacterium lactis Bl-04®. The probiotic supplement had a strength of 17 billion CFUs and was given over a 28 day period alongside standard antibiotic treatment. Patients in the control group were given a placebo.

The results of the study showed a reduction in the duration of the infection in the probiotic group, where symptoms (typically diarrhoea) were reduced by an average of 24 hours. As patients with C. difficile are often very ill, any reduction in the duration of their symptoms is extremely significant, as the infection can significantly lower their chances of survival and can also increase the risk of infection in other patients. The incidence of C. diff infections also places a financial and practical burden on hospitals, so any safe and viable solution to conventional treatment will be welcomed by hospital administrators and staff.

Another, double-blind study observed 44 critically ill patients with aim of assessing the positive benefits of another strain, Lactobacillus plantarum 299v® (LP299v®), on the incidence of C. difficile infection. The study was randomised, and subjects were to be given either a dose of LP299v® or a placebo. In the placebo group there was a 19% incidence of C. difficile infection, whereas in the probiotic group, none of the patients contracted C. difficile infection.18

A further study aimed to identify and track the genetic code of C. difficile strains taken from hospital patients, in order to better understand the patterns of worldwide spread and the rapid emergence of this bacteria. 151 samples of patients who died from or contracted C. diff between 1985 and 2012 were analysed, and the study involved specimens from 19 countries.13

The research found that two specific antibiotic resistant C. difficile strains known as FQR1 and FQR2, which were first identified in North America, were responsible for hospital outbreaks as far away as the UK, Europe and Australia. FQR1 originated in the United States and was found to spread to Switzerland and South Korea, and FQR2 started in Canada and spread to North America, Europe, the UK and Australia.

Using genetic techniques, researchers were able to identify different strains and created a family tree for C. difficile which made it easier to trace the movements of this bacteria globally. They were also able to test another 145 samples from patients in Britain specifically, in order to more closely understand how the bacteria was able to spread once it arrived in the UK.

The analysis found that the strains became more severe and easily transmitted once the bacteria became resistant to antibiotics. The research also highlighted how interconnected global healthcare services are around the world and how rapidly strains of the bacteria were able to travel between countries.

Can probiotics make C. diff worse?

There is absolutely no evidence to support this concern. C. difficile infections are most commonly treated with met*******ole or van****cin antibiotics. Whilst this treatment is effective for most, the disease does recur after therapy in 20% of the outpatient population.14 In these cases, multiple recurrences are common and can be difficult to treat,15 as C. diff strains can become antibiotic-resistant.

This is why many people are looking towards natural support from probiotics to be used alongside the antibiotic treatment, in order to replenish the body's natural friendly bacteria levels.

Faecal transplants and C. diff

It is a similar theory that drives the idea of a faecal transplant. Generally faecal matter of a relative will be used, preferably one who lives with the patient, as they are more likely to have similar gut flora. A small amount is taken and mixed with salt water before being transplanted to reach the patient's bowels. The theory behind this treatment is that the healthy faeces contain probiotic bacteria which will colonise and support gut immunity.16

There has been an average success rate of about 90%17 although the practice has only been carried out a small number of times, however, there have been exciting developments from Australia18 which has given regulatory approval for faecal transplants and from the USA where the FDA also approved the first faecal microbiota product for the prevention of recurrence of Clostridioides difficile infection. They are the first countries in the world to do this and it will be useful to observe what results they achieve using this method.

A 2022 case report on a pregnant women with C. diff found positive evidence for cross-generational strain transfer following FMT21. This case study may lead the way in providing novel insights into the dynamics and engraftment of bacterial strains from healthy donors.

But can probiotics mask C. diff? Once we understand their mode of action, in that they discourage the growth of pathogenic bacteria and create an environment in which these bad bacteria find it difficult to flourish, you can see that they will not mask C. diff but can support the gut microbiome to remain balanced.

Summary

In summary, probiotics have been shown to suppress Clostridium difficile and work well as an adjuvant therapy alongside antibiotics. When it comes to which probiotics are best for C. diff or what is the best probiotic to take for C. diff recovery there are a number of different strains that have been used in clinical trials and have been shown to be effective, including:

- Saccharomyces boulardii

- Lactobacillus plantarum 299v®

- Lactobacillus acidophilus NCFM®

- Bifidobacterium lactis Bl-04®12

If you look for a probiotic that contains some of these strains, you can be confident that with the current research it will be the best probiotic for C. diff recovery and equally one of the best probiotics for use with C. diff treatment.

You can find Saccharomyces boulardii in Optibac Probiotics S. boulardii, and Lactobacillus acidophilus NCFM®and Bifidobacterium lactis Bl-04® can be found in Optibac Probiotics Every Day EXTRA.

You can also have a look at our Probiotics Database for further research on these probiotic strains and C. difficile.

If you enjoyed this article, you may also enjoy reading the following:

Probiotics for Upset Stomach and Food Poisoning

References

- The Lancet Infectious Diseases. (2019). C difficile—a rose by any other name. . .. The Lancet Infectious Diseases, 19(5), 449. https://doi.org/10.1016/s1473-3099(19)30177-x2.

- NHS website. (2022, December 20). Clostridium difficile (C. diff) infection. nhs.uk. https://www.nhs.uk/conditions/c-difficile/

- McFarland, L.V. (1999) Possible role of cross-transmission between neonates and mothers with recurrent Clostridium difficile infections. Am J Infect Control. 27: 3:301-303

- Pothoulakis, C. (1996) Pathogenesis of Clostridium difficile-associated diarrhoea. Eur. J. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 8:1041-1047

- Dove, C. H. et al. (1990) Molecular characterization of the Clostridium difficile toxin A gene. Infect. Immun. 58:480-488

- Just, I. et al. (1995) The enterotoxin from Clostridium difficile (ToxA) monoglucosylates the Rho proteins. J. Biol. Chem. 270: 11074-11078

- Riegler, M. et al. (1995) Clostridium difficile toxin B is more potent that toxin A in damaging human colonic epithelium in vitro. J. Clin. Investig. 95:2004-2011

- Fekety, R. (1997) Guidelines for the diagnosis and management of Clostridium difficile-associated diarrhea and colitis. American College of Gastroenterology, Practice Parameters Committee. Am. J. Gastroenterol. 92: 739-750

- Barker et al (2017), A randomized controlled trial of probiotics for Clostridium difficile infection in adults (PICO), Journal of Antimicrobial Chemotherapy, dkx254, https://doi.org/10.1093/jac/dkx254 Published: 23 August 2017

- Castex, F. et al. (1990) Prevention of Clostridium difficile-induced experimental pseudomembranous colitis by Saccharomyces boulardii: a scanning electron microscopic and microbiological study. J. Gen. Microbiol. 136: 1085-1089

- Corthier, G. et al. (1986) Prevention of Clostridium difficile induced mortality in gnotobiotic mice by Saccharomyces boulardii. Can. J. Microbiol. 32: 894-896

- Corthier, G et al. (1992) Effect of oral Saccharomyces boulardii treatment on the activity of Clostridium difficile-toxins in mouse digestive tract. Toxicon 30: 1583-1589

- Miao et al 2012, ‘Emergence and global spread of epidemic healthcare associated Clostridium difficile’. Nature Genetics, 9/12/12.

- Fekety, B. et al. (1989) Treatment of antibiotic-associated Clostridium difficile colitis with oral van****cin: comparison of two dosage regimens. Am J Med. 86:15-19

- Surawicz, C. M. (2003) Probiotics, antibiotic-associated diarrhoea and Clostridium difficile diarrhoea in humans. Best Practice & Research Clinical Gastroenterology; 17: 5; 775-783

- Brandt LJ. Fecal transplantation for the treatment of Clostridium difficile infection. Gastroenterol Hepatol (N Y). 2012 Mar;8(3):191-4. PMID: 22675283; PMCID: PMC3365524.

- Lawley, T.D et al (2012) Targeted restoration of the intestinal microbiota with a simple, defined bacteriotherapy resolves relapsing Clostridium difficile disease in mice. PLOS Pathogens. Published online ahead of print.

- Shepherd, T. (2022, November 10). Australia gives world-first approval for faecal transplants to restore gut health. The Guardian. https://www.theguardian.com/australia-news/2022/nov/11/australia-gives-world-first-approval-for-faecal-transplants-to-restore-gut-health

- Wade, G. (2022, December 2). First faecal transplant treatment approved for use in the US. New Scientist. https://www.newscientist.com/article/2349578-first-faecal-transplant-treatment-approved-for-use-in-the-us/

- Al Sharaby A, Abugoukh T M, Ahmed W, et al. (August 02, 2022) Do Probiotics Prevent Clostridium difficile-Associated Diarrhea?. Cureus 14(8): e27624. doi:10.7759/cureus.27624

- Shaodong W et al., (2022) Cross-generational bacterial strain transfer to an infant after fecal microbiota transplantation to a pregnant patient: a case report. Microbiome, 10:193

- Van Nood, E et al 2013. ‘Duodenal infusion of donor feces for recurrent Clostridium difficile, The New England Journal of Medicine, 68, 407- 415. Published online January 16 2013.

Popular Articles

View all Digestive Health articles-

Digestive Health12 Jul 2023

-

Digestive Health17 Mar 2023